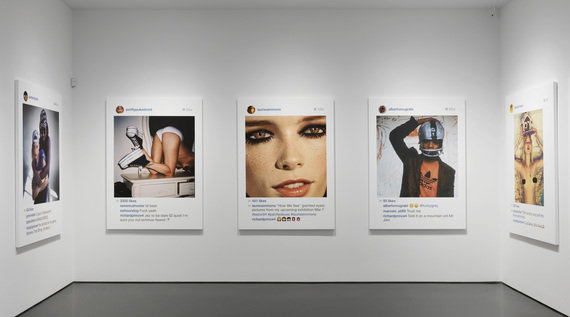

Richard Prince caused quite a stir recently by showcasing his New Portraits series at the Frieze gallery in New York. Originally debuted at the Gagosian gallery in 2014, New Portraits elicited a new wave of mixed reactions when pieces began to sell for over $90,000 each. The “portraits” are essentially blown-up screenshots of other people’s Instagram posts. They are mostly of women, and entirely used without the permissions of the original posters, who are for the most part internet celebrities in their own right.

Art critics and followers of Prince’s career argue that this technique of co-opting other’s images and exhibiting them as one’s own is nothing new, and has in-fact been an important element of Prince’s practice since his start in the 1970’s; repurposing images in print magazines by “re-photographing them” and altering them to create a new, if highly referential image commenting on the moment in contemporary culture.

“Prince, since his earliest appropriated works, has often been concerned with showing us cultural types. Is this what we’re looking at here? Various types of looks and poses and gestures and attitudes of contemporary portraiture on Instagram?” Asks Matthew Israel in an article for the Huffington Post.

However, what Israel fails to mention is the troubling pattern that appears in Prince’s work, his comfort in appropriating “types, looks and gestures” from predominantly female sources without their explicit permission. This reduction of the female visage to a series of symbols and cultural tropes without crediting the original artistry our autonomy of the posters reveals the dark undertone of dominance and ownership through the privilege of artistic status that cannot be denied in Prince’s work.

Prince represents the established artist. He is at the benefit of a convergence of identities that give his work legitimacy. His name and reputation allow him to sell these works for $90,000 a piece, and for the art world to say that they are an astute comment on the contemporary moment.

What this viewpoint fails to consider is that the Internet celebrities who generate Prince’s appropriated images are making their name in their own right using the selfie as a form of self-promotion and of art outside of the sanitized and often impenetrable world of the white wall gallery. Audrey Wollen, who has used the usurpation of her own images by Prince as an opportunity to talk about representation and objectification, talks about turning the lens inward as an act of ownership of her own objectification in an interview with Vice i-D:

On your Instagram, you describe an anxiety of being untouchable. Do you fear that documenting yourself as art makes you more of an object?

“Absolutely. I don’t even fear it anymore – I know it does. I perpetuate my own objectification every day. But I’m interested in the idea that objectification itself has radical potential—we can use the products of oppression as the tools to dismantle it. I wish I could just be a person, and not a walking photograph of a naked girl. But I wasn’t given a choice. I was being treated as if I was only a photograph of a naked girl long before I started taking photographs of myself naked.”

By using the Instagram images of others, particularly women, without their consent or permission, Prince attempts to reverse an act of defiance in a culture of objectification. He is re-asserting his power as tastemaker and validator of the worth of the bodies of others, perhaps as a way to maintain cachet as zeitgeist shifts value and in contemporary culture away from the favor of the established.