Colombia’s arte contemporáneo scene has received international recognition over recent years—something that could be attributed to the star power of heavyweights like Fernando Botero, Guggenheim’s Doris Salcedo, or young darlings such as Oscar Murillo who is revered as “the 21st century Basquiat.” A collective that forges art spaces deserving equal prominence is TIMEBAG, previously highlighted by Art Report situated in Medellín, Colombia. It acts as a nexus for artists and curators alike, serving as a tremendous innovative arena where the work produced transcends the constraints often associated within gallery walls. Here the city’s next generation of artists are cultivated and revealed.

The frontrunner and Medellín native, Fredy Alzate merges the concepts of art and architecture. His most recent work Scarabaeus Laticollis (or dung beetle), made of recycled tires at a staggering 2.5 meters in diameter, echoes the sentiments of urbanization in his city and ultimately Latin America. As part of the World Summit on Arts and Culture, the diligently executed, monumental sphere was displayed in San Juan de Dios’ Hospital; reappropriating one of Medellín’s oldest and most poignant buildings. Seduced by the spectacle, the immense structure appears smooth and approachable at first glance, yet the sheer size is bold and contradictory to this belief. Upon closer inspection imperfections are evident, acting as a metaphor for the uncontainable urban development, where the urgency for new builds is rife. His work reveals the tenuous culture of congestion and apparent challenges the urban peripheries of Latin America face.

By comparison, medical surgeon and artist Libia Posada’s work warrants a deeper understanding. Drawing on her experiences, Posada has carved out her own existential relationship between medicine and art. The series of works question ambiguous notions such as reason and madness, health and disease, beauty and horror, strength and fragility, public and private. Earth and Salt Herbs or Studies for Dystopic Cartography, shown at Museo de Antioquia as part of art fair 43SNA (Salón Nacional de Artistas), depicts a sterile Ikea-esque hospital room, sprinkled with botanical medicine, cabinets and narrative photography. She explores the relationship between the body and geography, focusing on Chocó, a region in the west of Colombia known for its large Afro-Colombian population. Her work with communities in remote areas of the country serves as a basis for artistic exploration.

Guiding the force is TIMEBAG director and artist, Harold Ortiz, who creates work across a variety of mediums. Ortiz’s work with steel on a large scale is particularly engaging, his main focus is on space and time as a collective. His fascination with the chemical reaction between the raw material and oxidation has shaped his artistic practice. He interrupts the natural deterioration of the metal; the final state is sped up and determined by Ortiz himself. Victor Garcés also relies upon local raw materials when creating work, this reappropriation of objects has come to define Colombian contemporary art. Initially, Garcés’ mélange of pictures, testimonials and charcoal appear to be nothing more than a pile of junk —then the authentic value of the work is recognized and the hybrid arises through drawing, installation and video.

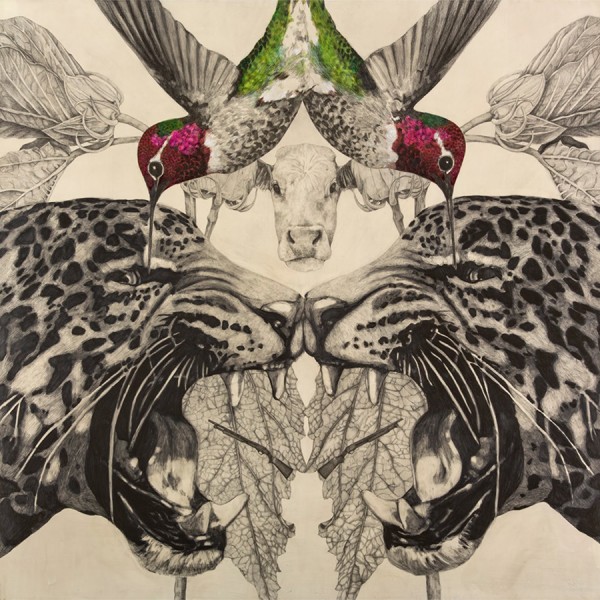

Meanwhile, Sara Herrera, emerging artist and nature enthusiast, redefines negative spaces with feline figures. Herrera addresses the complex relationship between humans and animals, creating a new dialogue of tension. Aquí portrays the silhouettes of big cats who have been displaced from their natural environment. They have been forced to leave and venture into the concrete jungle. The sense of movement in the work demonstrates the dramatic reduction of their habitat, near the city of Medellín. Beast or human, the search for an alternative space is paramount.

Like this article? Check out At The Forefront of Colombian Contemporary Art: City of the Eternal Spring (Part 1) and other global art initiatives.