We have long accepted cities like London and New York as frontrunners in the global art scene; likewise, we’re familiar with art prowess in Istanbul, Brussels, and Detroit. Recently, however, our attention has been shifted to cities that one might not typically associate with a thriving art market. One such place is Colombia’s second largest city, the metropolis of Medellín.

The country itself has had a vibrant art scene for many years, but a recent influx of foreign influencers in the country has stoked international presence here, spurring a new dialogue for Colombian contemporary art and, in turn, encouraging the rest of the art world to follow suit. Where there was an equivalent phenomenon in China and Brazil not too long ago, Colombia is fast becoming a global art hub. Respectfully, Medellín is spearheading this movement. Situated in Aburra Valley and surrounded by a string of mountains clad in dense forest, “The City of the Eternal Spring” is gaining recognition for its innovation in Colombian contemporary art, caught in a moment of reinvention and ridding it of its dark, controversial past.

X Contemporary, Miami expertly highlighted endeavors such as TIMEBAG, an independent contemporary art project, which serves as a great example of a city on the cusp of change. Founded in July 2014, the project provides a pivotal platform for alternative exhibition spaces in Medellín; a hub where contemporary art is shared in a less conventional manner, concentrating on the experience as a whole and in doing so, bringing art closer to its spectators. With Colombia’s innovative spirit in mind, we asked TIMEBAG Director and Artist Harold Ortiz to give us his take on the development of Colombian art – specifically that of Medellín – and elaborate on the ethos behind his inspiring project.

Art Report: We’re fascinated by the fact that you’ve removed yourself from the traditional gallery arena and sought alternative spaces, like abandoned hospitals and derelict train stations outside of the city to showcase exhibitions. Why was it important to work outside of the center of Medellín?

Harold Ortiz: There are very good contemporary artists in Colombia, but there aren’t very many galleries. There are also contemporary art projects that don’t really fit into a gallery, and there aren’t galleries that are big enough or with a suitable infrastructure to host this type of project.

When I was in New York in 2012-2013, I was able to witness that these type of projects were being done everyday. When I went back to Medellín, I decided to start looking for a series of alternative spaces—where initially it was a personal process, an individual exhibition. Basically, I work with very large pieces and I wanted to find a space that would allow me to create a specific piece, and this is when I found the “Ferrocaril de Antoquia” (Antoquia Railway Station). It was a conjunctural, rare moment and something which emerged spontaneously. I was looking for new places to exhibit, and the city was looking for new propositions in an art context. This was the moment where everything clicked and TIMEBAG turned into the project it is now. Both the city and Colombia were waiting for this type of transition.

Finding the location was a spontaneous and organic occurrence because the city was also looking to develop the contemporary art scene and exhibit these types of works to the public.

AR: What we love about TIMEBAG is you seem to be encouraging not only emerging artists to get involved but the public too—you’ve created a particularly sincere atmosphere. How did you achieve that?

HO: I first started TIMEBAG with the intention of looking for alternative spaces, because of the economic, social and political issues over the past two decades in Colombia. Now, artists and the public come to us with suggestions, like the abandoned hospital of San Juan De Dios. They share their issues and open the doors for discussion through art.

We understand that art in these moments is in the search for different audiences, much like other industries. Art is not just about creating pieces; it is as much about the public being able to consume it. This is currently the dilemma which many museums and galleries face. It is a question they are asking themselves: What do I do to attract more people? We think we have found communication channels that would not typically be used by traditional exhibitors. A museum would never advertise on the radio. They would never use mainstream media, which does not specialize in art. We have set ourselves to find the channels, to reach the public who don’t have an affinity for contemporary art and to invite them to come and have a discussion with us. When we bring the public to a contextualized place (socially, politically or economically), and we bring artists with a piece conveying an opinion, a dialogue starts, and this is when the art actually begins.

In Colombia we have heavy use of digital channels, we make strong partnerships through social media and we talk a lot with bloggers. We have a strong digital structure and focus on entertainment factor. We know that an audience that does not know much about art will not be looking for something specific but rather searching for something entertaining, something that will surprise them. In being there, they discover the work and the artists. Then questions arise.

AR: How have you created the dialogue between the public and the art?

HO: This is sort of a personal challenge. We are artists, and we understand that the relationship between the piece and the audience is very important. In Colombia, the majority of the artists have an academic orientation, therefore the challenges are different. For me, art is a tool for thought more than a commercial or aesthetic objective, and we can somehow pass this tool on to change a society. That would be the real success of the project, enabling change. It is a challenge everyone in Colombia is facing and we are doing it from an art front.

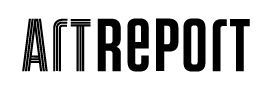

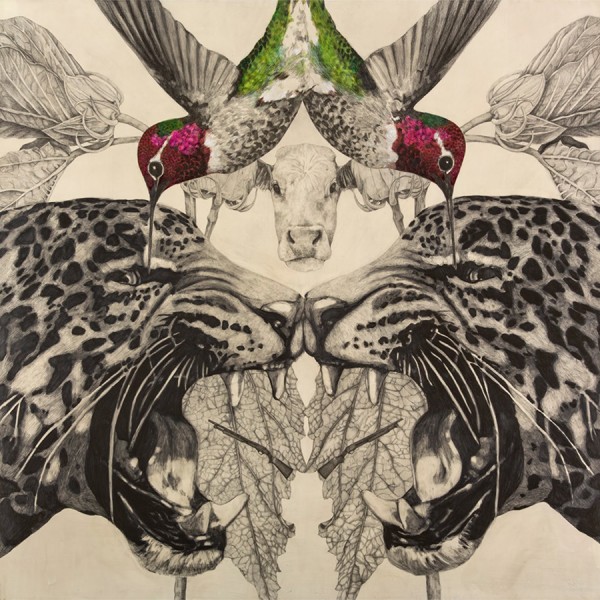

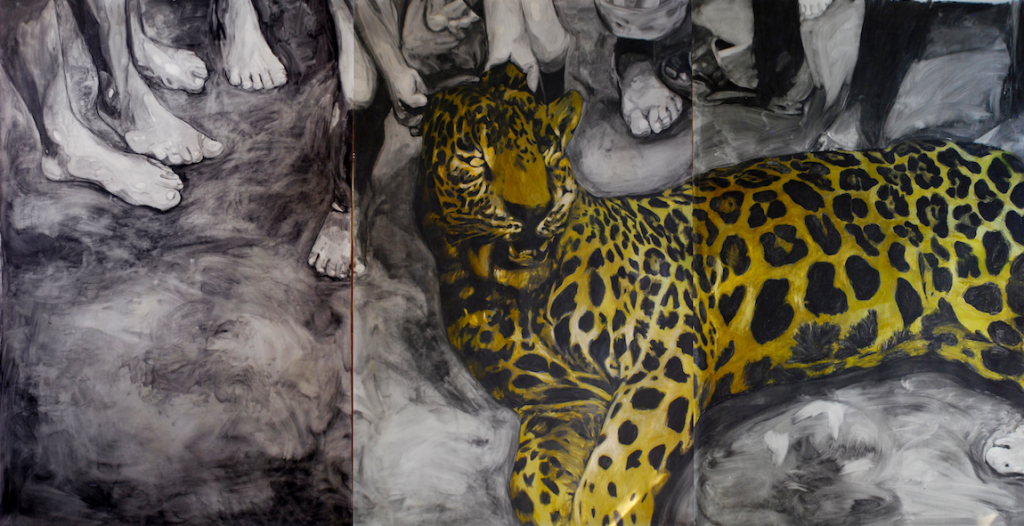

AR: Tell me about TIMEBAG: Colombia N.O.W. and how you represent contemporary Colombian culture through art?

HO: The space and the place are the protagonists of our projects so being in an art gallery doesn’t actually fit with what we usually do. With the curatorial committee, we decided that the territory and the space should be an emotional one. What better moment to talk about a country than when it is really in an integral moment of transition? This is the reason why the curatorial committee invited a series of artists to talk about key topics/themes that are relevant and central to the country in the last two to five years. It is here that a very interesting opportunity emerged. The response of the artists and those within the network of national art were all very good. So it was an opportunity to create an emotional space and Colombia just happens to be that space.

AR: There has been an obvious emergence of Colombian artists in the last decade, can you elaborate on this boom?

HO: There is much attention at the moment on Latin American Art, particularly on Colombian art. I think a lot of it has been influenced by the fact that in the last two decades we (Colombia) have been very closed. This is not to say that during this time art was not being made, but there was no dialogue with the outer world. The artists that have been featured in auctions in New York or exhibited in museums are actually artists that produced worked three decades ago. Now there is new generation of artists that have had the opportunity to travel or study abroad in New York and London, return to Colombia and have been able to start a conversation about local thought with a universal discourse. This is when the international market realized that there is something interesting going on here. I think this is just the beginning of the commentary about Colombian contemporary art. We are only just seeing the tip of the iceberg of what has begun to cultivate among the past two generations of artists and the community. People who speak two to three languages, generations who have come and gone to other countries and know that there are millions of stories to tell—not only about Colombia but also about Latin America. In one of the articles that I read, they commented that Colombian art has the ability to tell stories beyond just the conceptual and aesthetic connections, and I think we have this need to tell millions of stories that we have unwillingly saved for the last two or three decades as a country.

TIMEBAG, just over a year old, is already making waves within the art world, demonstrating that our appetites are transforming and swaying in favor of Colombian contemporary art. Read part two next week as we take a closer look at Colombia’s emerging artists.

Like this article? Check out the highlights from ARTBO: The Premier Art Fair of Latin America, or highlights from other art fairs.