The new Whitney Museum, built by Renzo Piano, now stands proudly at the southern end of the High Line in New York. American art can now be appreciated from multiple perspectives as the building assists you in your exploration with bright expansive indoor galleries and fantastic outdoor terraces.

Now that the dust has settled around the museum’s opening, we want to help visitors navigate the 650+ works of art. America is Hard to See can be overwhelming, so we have created a two-part art adventure that thematically connects works from all 4 floors of the museum. Our first installment, The Age of the Machine, explores the narrative of industrialization and the role of technology throughout American art of the 20-21st centuries.

Before we begin our “tour”, one notable perk is that even the elevators are part of the artistic ambition of the museum, as all four of the elevators are the work of the artist Richard Artschwager (his last before he died in 2013) and each offers its own whimsy with materials and effects.

Take one of the elevators all the way to the 8th floor and start from there.

Joseph Stella, The Brooklyn Bridge (1939)

Joseph Stella (1877-1976) was the ultimate American artist: an Italian immigrant who was enthusiastic about European artistic influences (particularly the Italian Futurists) but nonetheless glorified American industrial and technological achievements.

Stella’s Brooklyn Bridge is a glorification of man’s creation, as lights and cars race along the bridge while Manhattan’s skyscrapers are glimpsed through the gothic arches. Though the bridge is a solid metal construction, Stella utilizes saturated, nearly translucent colors that create an effect that is reminiscent of stained glass windows. By celebrating industrial achievements in an altarpiece like composition, Stella simultaneously salutes both his heritage and his new-found country’s technological future.

Don’t go too far yet, just to the right of Stella’s painting you will see a hanging mobile sculpture.

Alexander Calder, The Spider (1939)

Alexander Calder (1898-1976), is the Pennsylvania-born artist who liberated sculpture from its static floor position it had occupied for several millennia.

The Spider’s black-painted metal body speaks to the fascination with industrial materials that Calder shared with his contemporaries in the 1940s and 50s. However, it also explores the human side of objects, as the mobile swings with the air current, creating the presence of a living creature. (Also, be sure not to miss Calder’s famous “Circus” on the 7th floor, which he both made and performed with from the 1920s on…)

Now head to the 7th floor by walking down either the inside or outside staircase.

George Tooker, The Subway (1950)

George Tooker (1920-2011) was one of the prominent Symbolic Realist artists. His work often lamented the state of modern society and its oppression and dehumanization.

We have all experienced traveling by subway in New York, but Tooker brings the discomfort to a whole new level. Here, the subway feels more like a prison, where eye contact is averted amongst commuters, and low ceilings increase the blatant sense of fear and distrust. Tooker seems to express the isolating social climate of the post-war 1950s.

Now walk through the smaller galleries into the expansive space by the terrace where we find the biggest players of Abstract Expressionism movement.

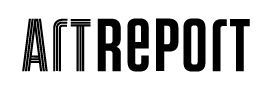

John Chamberlain, Velvet White (1962)

John Chamberlain (1927-2011) is associated with the Abstract Expressionists but lived long enough to move beyond its initial impulse. You will never mistake his sculptures for anyone else’s, as the early versions were always made of found car parts. Chamberlain initially explained that he turned to this material when he “ran out of iron rod” – but it most certainly also represents the virility of American industrial achievement.

Velvet White takes on an almost figurative, anthropomorphic form that inspires awe at his ability to compress, bend, and mold this powerful material into gestural shapes. The true age of the machine comes through in Chamberlain’s works, as with many of the other Abstract Expressionists, whose angst-ridden forms of art came to symbolize the psychologically traumatizing effects of World War II.

Before walking to the 6th floor, stop by the outdoor terrace to see the three metal sculptures juxtaposed with the urban background view of New York City.

David Smith, Lectern Sentinel (1961)

David Smith (1906-1965) is considered one of the most important sculptors of the 20th century with his stainless steel works that are both monuments to the machine age and personal reflections upon figures in a landscape. He was greatly influenced by Pablo Picasso and sometimes named his sculptures after his daughters.

Look closely at the burnished surfaces of the sculptures which are finished to playfully catch the light and look a bit like brushstrokes on metal. David Smith was a initially a painter before he became inspired by industrial materials.

The 6th floor offers a release to the tense emotions found on the 7th floor, with works by Minimalist, Conceptual, and Pop Artists.

Richard Serra, Prop (1968)

Richard Serra (b. 1930) is known for his monumental installations and sculptures that we, as tiny observers, sense through our bodily interactions. There is always a great sense of tension generated as his massive sculptures engulf its viewers. Serra utilizes industrial material that are meant for urban building and poetically alters them to serve his artistic cause.

Though “Prop” is significantly smaller than the monstrous sculptures Serra is known for, the obvious tension remains as the heavy piece of metal balances against the wall. Serra always focuses on the words that describe his creations and often writes up a list of verbs and actions before he names a piece. Here, “Prop” stands for the action of the piece and the object it represents.

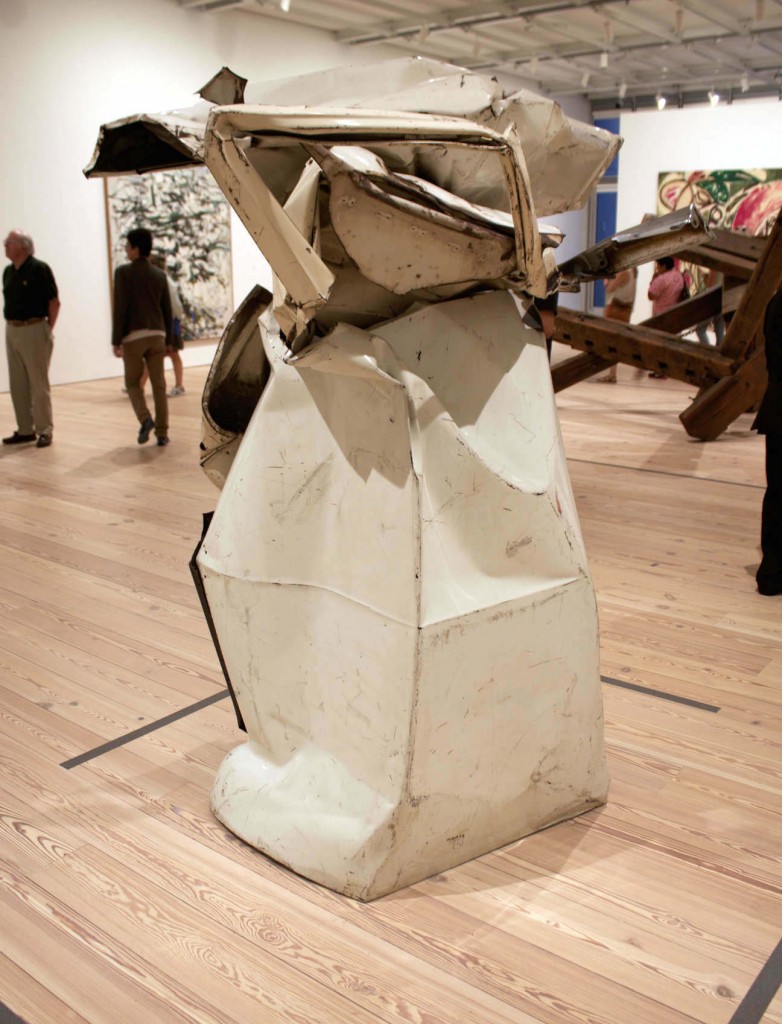

Andy Warhol, Green Coca-Cola Bottles (1962)

Andy Warhol (1928-1987) exemplifies the influence of mass production and consumer culture in the machine age better than anyone else. He sought to glorify and depict objects in a way that made them feel so familiar, yet easily interpreted in multiple ways. Further, his work itself seems to be mass produced until one looks closer at the images and realizes that each work contains inconsistencies and slight imperfections.

One of the best quotes by any artist that truly speaks of the glory days of American culture is by Warhol on Coca-Cola:“What’s great about this country is that America started the tradition where the richest consumers buy essentially the same things as the poorest. You can be watching TV and see Coca-Cola, and you know that the President drinks Coca-Cola, Liz Taylor drinks Coca-Cola, and just think, you can drink Coca-Cola, too. A Coke is a Coke and no amount of money can get you a better Coke than the one the bum on the corner is drinking. All the Cokes are the same and all the Cokes are good. Liz Taylor knows it, the President knows it, the bum knows it, and you know it.”

Lee Bontecou, Untitled (1961)

Lee Bontecou (b, 1931) produces work that inspires you to shrink back at their aggressive nature and mechanical parts, leaving some viewers a bit surprised upon realizing these antagonistic sculptures are the work of a female artist.

In the above, Bontecou used salvaged machine parts and canvas from conveyor belts of the neighborhood laundromat to stitch her mysterious and somewhat baffling wall sculpture. Her work was very representative of the darker side of the 1960s, as she expressed aggression, war, and the fear of mankind’s self-destruction through nuclear conflict.

Our final leg of the tour brings us to the 5th floor, where the more contemporary artists utilize technology as their mode of expression.

Nam June Paik, V-yramid (1982)

Nam June Paik (1932-2006) is largely considered to be the father of video art. Born in Korea and trained as a classical musician, he conceived his art form as a reflection of our machine age.

The V-yramid was made by the artist for his retrospective at the Whitney museum in 1982. Here Paik draws comparison between the grandeur of an ancient monument and artistic enlightenment through our common entertainment machine. He sought to elevate the TV to a mythic status, explaining, “I wanted to elevate television to an art form that was as highly valued as the music of Johann Sebastian Bach.”

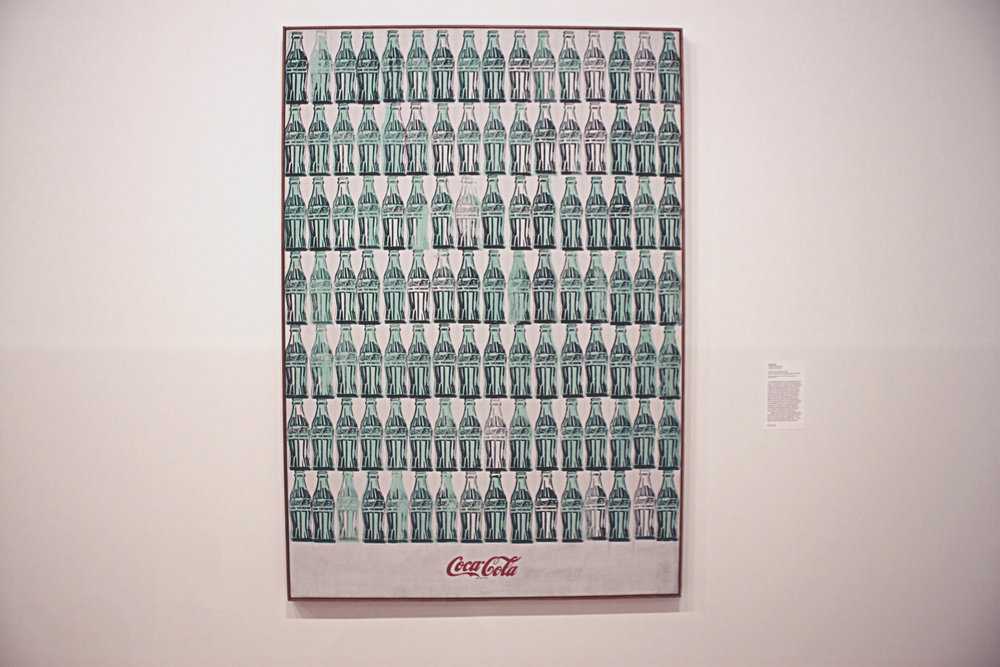

Paul Chan, 1st Light (2005)

Paul Chan (b. 1973), like many of his contemporaries, delves into many mediums to express his ideas and philosophy.

1st Light is projected in a dark room onto the floor, that upon first site appears seemingly innocent as the shadows of birds fly by. As minutes pass, objects begin to rise up: first cell phones and then cars and other debris that break apart as we watch them. Suddenly, falling bodies begin to cross the floor as the tragedy becomes clear. The ghosts of our collective memory loom in this beautiful and eerie projection, as the artist laments the destruction caused by machines and our loss as a culture.