Renowned for her collaborative art and social activism, Yoko Ono has maintained a cardinal force in the art world. She has an artistic potency that is both poetic and profound, often engaging with her audience via “instruction pieces.” This tryst between art and society, visitor and artist, is the crux of her newest show The Riverbed. Occupying both Galerie Lelong and Andrea Rosen with identical installations, The Riverbed invites visitors to reflect over river stones, mend broken ceramic, and discover the infinite through line drawing. Due to the work’s interactive nature, the two installations evolve over time, departing from their parallel forms into two ostensibly different shows. The process is an anthropological study as much as an art show. Under the guidance of Ono’s tonic guidelines the audience undergoes intrinsic transformations of perception; she sheds Hikari (light in Japanese) on our acuities and inspires us to question established modes of thought.

Working in tangent with one another, The Riverbed galleries betoken an allegorical village, functioning as a crossroad for healing. She speaks directly to the soul of the viewer; as such, her art is a medium between consciousness and transcendence.

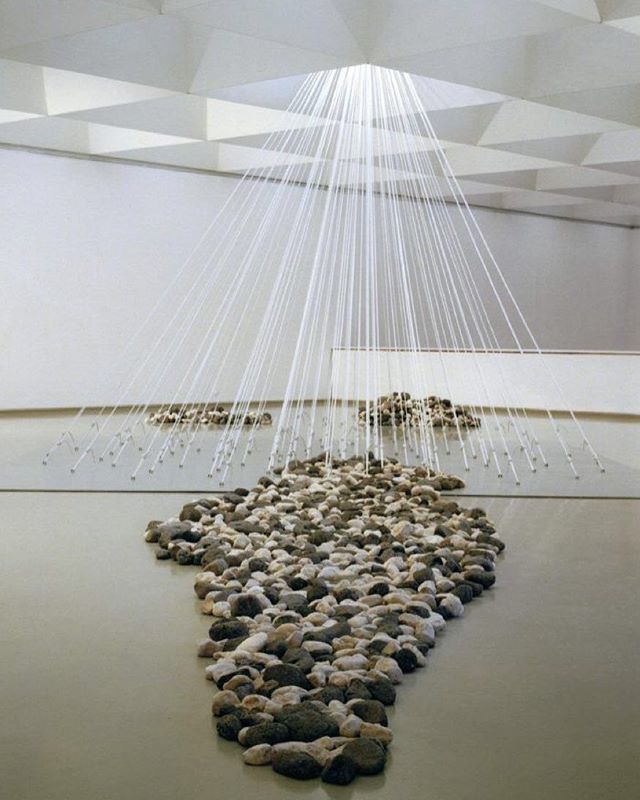

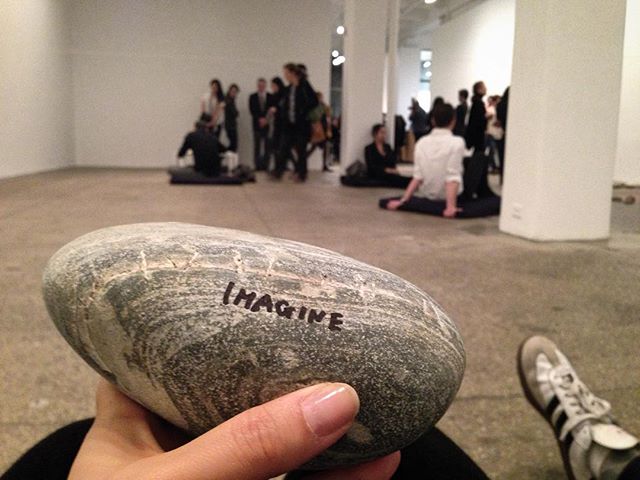

In “Stone Piece,” Ono has gathered, smoothed and sprawled out river stones on the floor. Per her instructions, you choose a stone and hold it until “all your anger and sadness have been let go.” Some have words inscribed like “imagine” and “dream.” Although this makes them somewhat doctrinaire, they are meant as meditation tools for restorative processing.

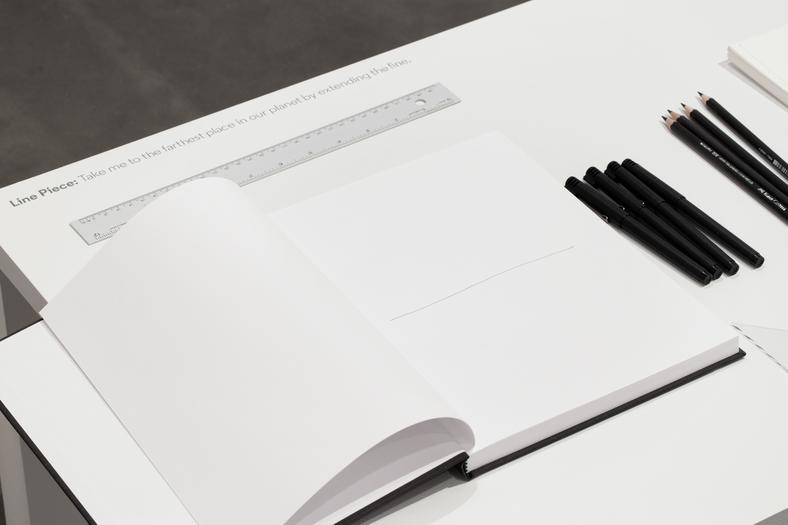

“Line Piece,” another debuting work, is comprised of twine converging the gallery walls and desks, topped with measuring kits next to large sketchbooks, instructing: “Take me to the farthest place in our planet by extending the line.”

Finally, her famed work “Mend Piece” is a welcomed old piece revived in the Riverbed village in both galleries’ tangential rooms. Visitors are encouraged to tape, cement and string ceramic fragments into their original form – to form many pieces into a single whole. Once repaired, there is coffee to enjoy and to signify the communal space of the village, to relish in the metaphysical mending of cracks in world misfortunes.

The truly fascinating feature of the installations is their contrasting facades. How the two galleries have evolved into radically different artworks under a single week. In other words, the interactive nature of The Riverbed allows visitors to overtake Ono’s artistry through a Barthesian form of semiosis. The installations, although first designed by Ono, are subject to the anonymous hands of many: At Lelong people placed the river stones in neatly formed worship circles, whereas at Andrea Rosen the stones were clumped together dappled with precarious cairns. Then there is Lelong’s “Line Piece,” comprised of labyrinthine lines in the sketchbook, while Andre Rosen’s extended more freely onto the walls themselves, pursuing abstract mountain tops and other indefinable doodling.

The most palpable difference was evident in both galleries’ “Mend Piece.” At Lelong, the visitors rendered the shattered ceramics into origami-like swans or modernist Arp-like fictions with twine wrapped aplenty. Andre Rosen featured more layered combinations, taping random pieces into makeshift forms. There wasn’t much mending as there was passionate execution with no forbearing trend in either. The mending was an anarchical form of harmony, a paradoxical development of a given task.

Ultimately it was, as all of Ono’s works so perfectly become, a reflection of the visitors’ narratives: what makes us find inner peace, what tickles our rage, what allows us to enter quietude and unearth beauty in the interconnectedness of the world. This show exhibits the poignant nature of those discoveries, and in every reverie of every mended crack, we find ourselves pieced together, orchestrated in solidarity by virtue of our human condition.