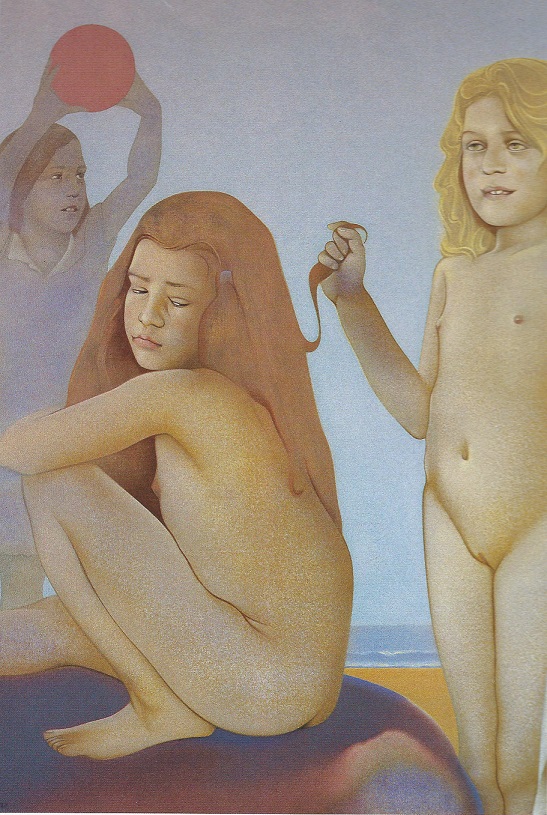

The story of Graham Ovenden is a story of a culture contradicting itself. Ovenden is an established and renowned artist in Britain, his works were hung in the Tate as well as the Victoria and Albert Museum, and sold for over £25,000 each. Throughout his career, his most famous subject matter has been suggestive nudes of young girls. Recently, most of Graham’s collection has been ruled indecent by district judge Elizabeth Roscoe, and aside from a few works, including a piece commissioned by Princess Diana that will be auctioned off for charity, most of it will be destroyed.

The cause for the art’s destruction is a new interest in the motivations behind its creation. The court claims that Ovenden’s motivation in the creation of his art was a sexual interest in children, the same art that was collected by the Tate and the V&A Museum. The art itself has not changed. A retroactive feeling of unease has taken hold on the subject of art that was now produced more than thirty years ago. The circumstances of its production, now officially deemed immoral by the British court, go from unspoken taboo to convicted crime.

Ovenden’s Subjects, who were under his care in the 70’s and 80’s, were surprised that it has taken this long for the artist to be convicted of sexual abuse of children. Ovenden had powerful names in the art world on his side, including Sir Peter Blake and David Hockney.

Pedophilia as an artistic subject has had its hold on culture for a long time, from the young boys that preoccupied Caravaggio, to Nabokov’s infamous Lolita. Culturally, we have become desensitized to the exploitation of young subjects by artists, writers, directors and producers of culture. Miroslav Tichy, an outsider artist who made his own cameras, regularly photographed young girls bathing and relaxing without their knowledge or consent, and those photographs became famous after his death, proving that the artist shared his personal obsession with a larger cultural zeitgeist.

The objectification and sexualization of underage subjects is a preoccupation that is expressed by individual artists, but it is a representation of the cultural callousness of the subject. This attitude of turning a blind eye is one that at best allows sexual exploitation to be overlooked in the repertoire of great artists, and at worst underhandedly encourages the pedophilic gaze of older artists through the sexualization of children in the context of art or literature.

“The collection of photos appears to me to disclose an obsession with naked girls,” said District judge District Judge Elizabeth Roscoe. Ovenden himself has called the whole affair “a witch hunt.” Judge Roscoe acknowledges that she probably will not be looked on favorably by the arts community after calling for the destruction of the work of a renowned artist, as well as irreplaceable historical photographs that were also a part of Ovenden’s collection.

However, it is important to remember these images, retroactively deemed predatory, were considered to be of great monetary and cultural value before Ovenden’s conviction of sexual offenses against three young girls who had modeled for his paintings. The British court’s decision to destroy the work of Graham Ovenden will do nothing to retroactively reverse the damage that the artist has done to the lives of children, and by trying to erase his cultural footprint, instead of inviting critical discussion of the art in relation to the exploitation of children, the British court is trying to sweep problems under the rug in disgust instead of engaging with their stubborn cultural foothold.

Like this article? Check out this interview of artist Elizabeth Yoo that explores pleasure and pain in her artwork, or other intriguing artist interviews.