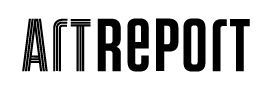

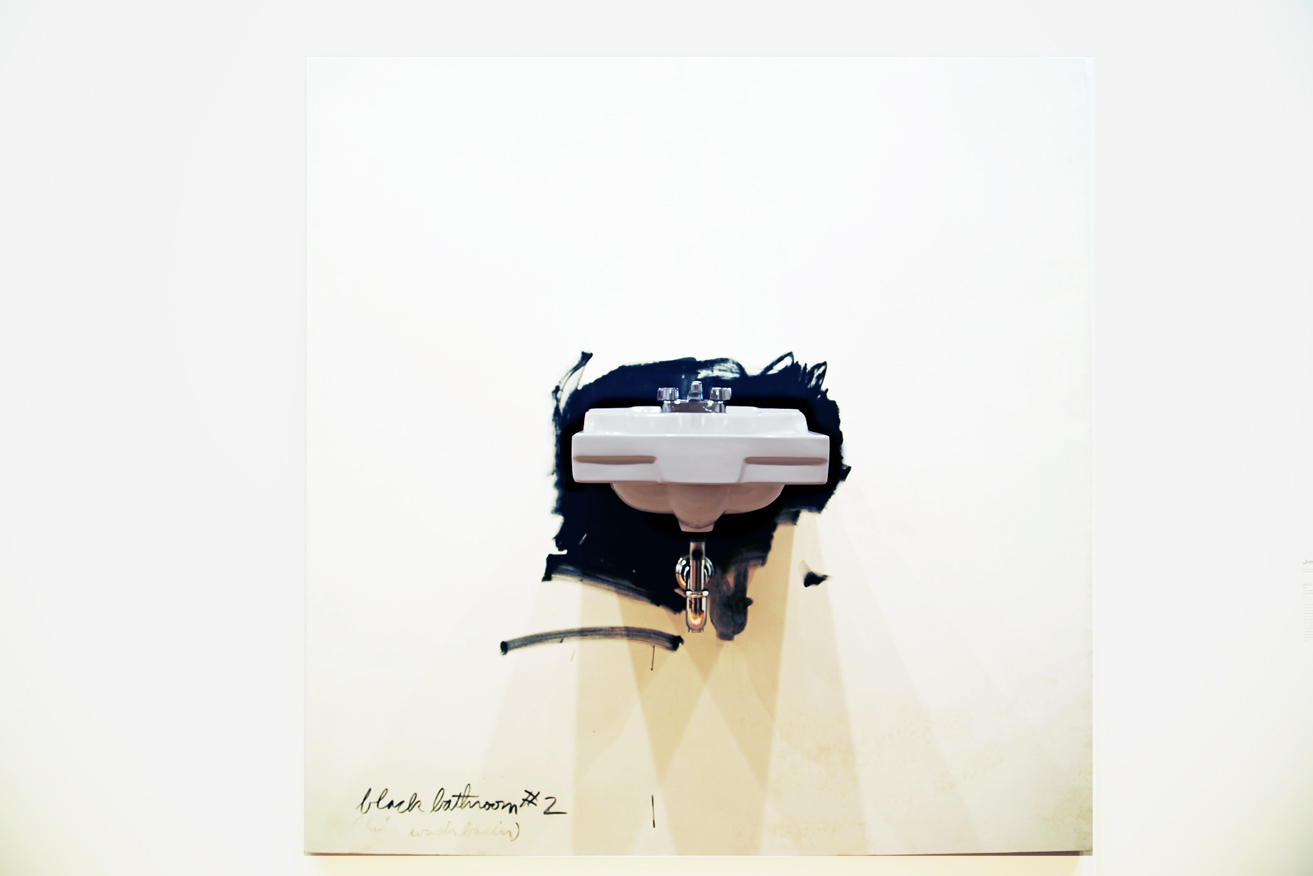

There’s a couple of bright Elvises, Cleopatras, a sink on the wall and a burger on the ground competing for your attention. Pop art was born from a consumer society, and lives for the insatiable materialism and the gross inflation of the ordinary, the fascination and spotlight for the every day. The Art Gallery of Ontario launches its new permanent pop art collection SuperReal which presents pieces from Claes Oldenburg, Andy Warhol, Roy Lichenstein, James Rosenquist, and Robert Rauschenberg to showcase the “excessive visual stimulation of this new world.” All of the pieces are gifts of or were purchased with the assistance of the Gallery’s Women’s Committee in the 1960s.

Your eyes can’t help but dart straight to the massive burger on the ground. Claes Oldenburg’s Floor Burger keeps up with pop art’s simultaneous affinity and mockery of capitalist economy and gluttony. It is a large scale soft sculpture (and you can’t help but want to leap and plunge into it) that was created for the 1962 installation of The Store, at the Green Gallery in Midtown Manhattan. “It seemed perfectly natural to me to that, if you’re going to make sculpture out of real things around you, then why not try to make them soft, so that you can push them around and they’ll change shape?” The Store sought to create dialogue around the ambiguities and contradictions of the market, and show “not just the buying and selling of cans of soda, but the buying and selling of heart.”

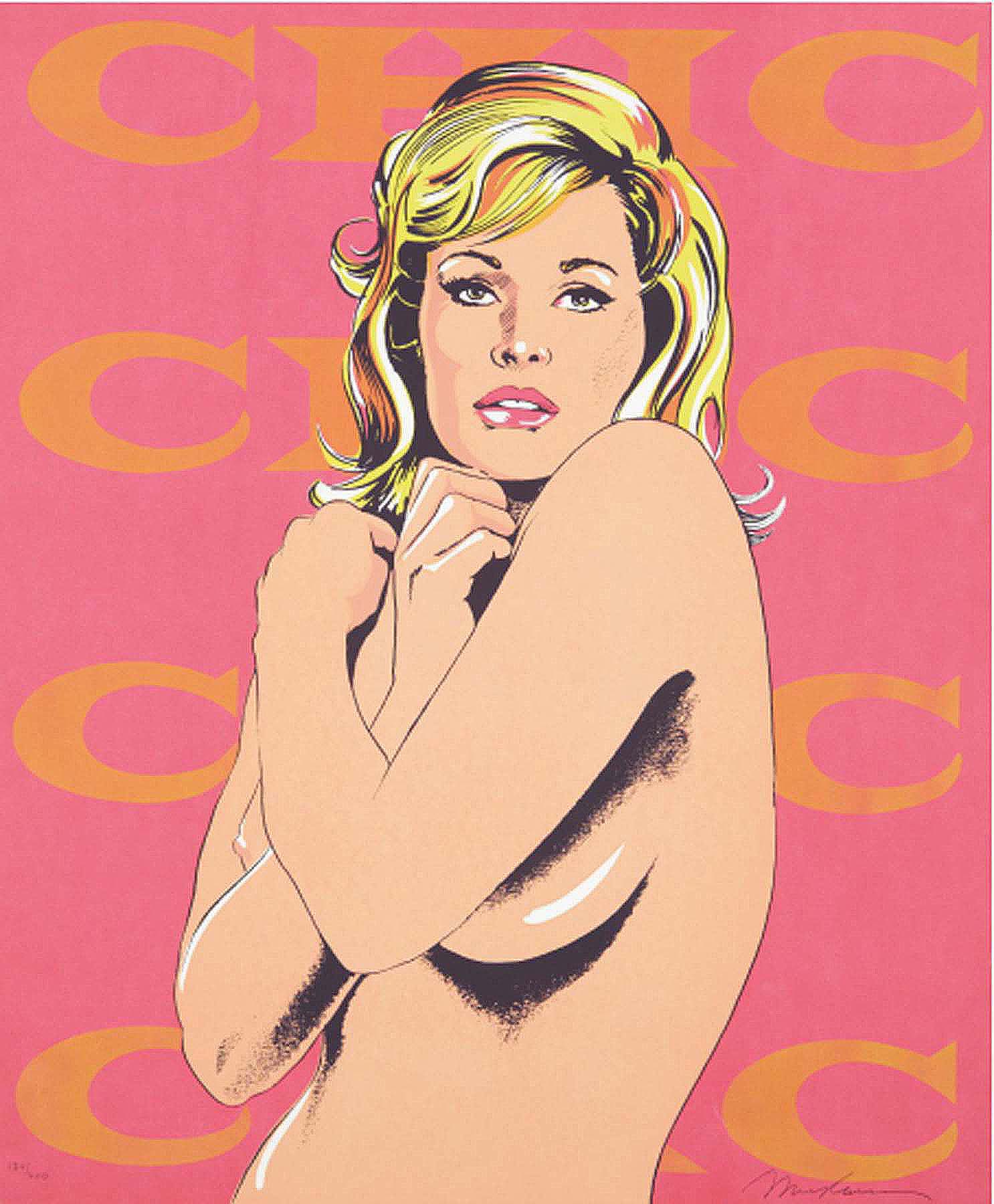

Are these Pop depictions of women exploitative or critical of the way we look at one another?

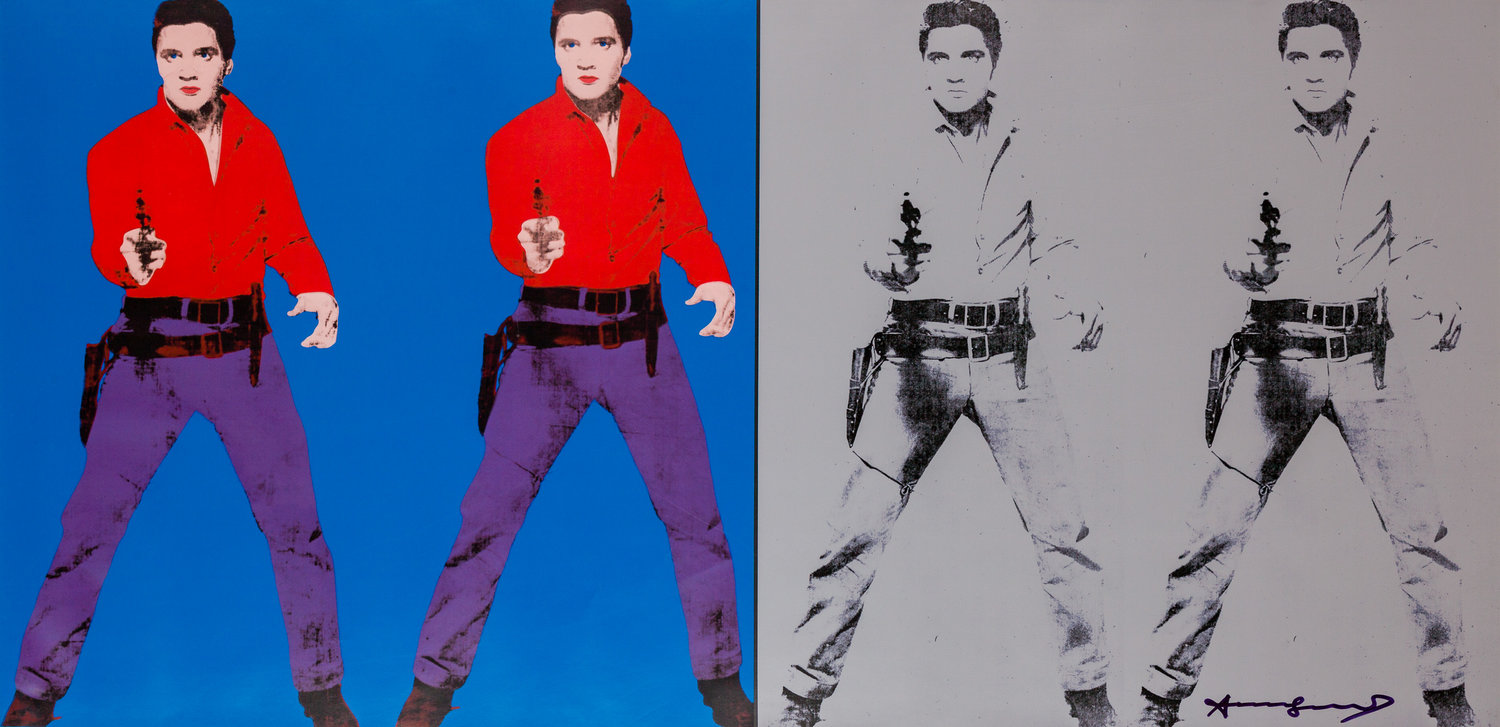

The open room funnels into a side cove, the attached Robert & Cheryl McEwen Gallery, and the AGO attempts to stimulate conversation with this prodding question printed on the wall as you enter it. I keep this in mind as I float around the cove, where British and American Pop Artists Andy Warhol, Roy Lichtenstein, Mel Ramos, Allen Jones, Richard Hamilton, James Rosenquist and Eduard Paolozi show images with inspiration taken from women from cinema, print, advertising and comics.

It is hard to imagine these female muses as sexualized objects ready for “quick and easy” visual consumption. If it were so quick and easy, we wouldn’t be here with this dialogue to begin with. Pop art in itself is more of an exploration than an oblique criticism of popular culture. There is a mockery, but it is intertwined with an affinity and admiration for the consumption of the glamorous or popular. Going around the room, the women are the focus, and they are free, powerful, present. The pieces follow aesthetic modes of media and advertisement, and the female muses are more released than exposed.

For example – James Rosenquist’s “Somewhere to Light: Waco, Texas”. In an interview with the Metropolitan Museum of Art, Rosenquist remarks “the ambiance of the painting is involved with people who are all going toward a similar thing.” “Going toward what?” asks the interviewer. “Some blinding light, like a bug hitting a light bulb… All the ideas in the whole picture are very divergent, but I think they all seem to go toward some basic meaning […] The picture is my personal reaction as an individual to the heavy ideas of mass media and communication and to other ideas that affect artists. I gather myself up to do something in a specific time, to produce something that could be exposed as a human idea of the extreme acceleration of feelings.” The print is a treasured memory of a wide, genuine smile. The female muse is released, not exposed. She is drawn to the light, and you to hers.

To say that these images are exploitative is to say that the uninhibited free behavior is one to be concealed. Arguing that these images of women are erotic suggests that they are inappropriate, the women are helpless, they are being taken advantage of, and safety is found in modesty. To think these images are exploitative is to say sexuality is private and only exposed for profit or advantage.

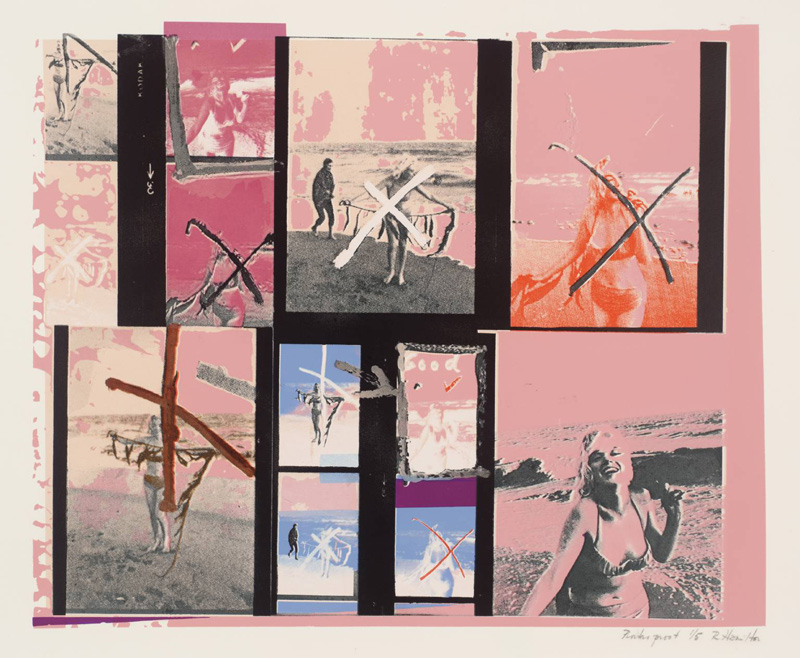

At first glance, Richard Hamilton’s My Marilyn seems like a possessive intrusion on private memories; an inappropriate scrapbook. I then started to see preserved happiness rather than exploitation. It was a homage, a respectful collage. Hamilton appropriated publicity stills of Marilyn Monroe published in a British magazine after her suicide. He committed to respecting Monroe’s own hand-drawn X’s, and did not to make any marks of his own, choosing instead to create painterly effects by enlarging, masking, screening, and overprinting.

Exploit as a noun can suggest something altogether opposite – a daring exploit of art could be a feat, an adventure, a stunt. Do I think these images are exploitative? No. Do I think these images are exploits of freedom? Yes.

What are your thoughts? Join in the conversation at #AGOasks.

Like this article? Check out Odili Donald Odita’s paintings at Jack Shainman Gallery and other global art news.