After a successful run, the Tate Modern will soon close their Agnes Martin retrospective in London. In case you weren’t able to weather the long lines, here’s a comprehensive break down.

The exhibition presents Martin’s paintings chronologically, with each room dedicated to a moment in the artist’s life. The Tate structured the exhibition almost ideally, with short biographies detailing each decade in order to help viewers understand her process and vision. The curators seem to have attempted to avoid the gritty details of Martin’s struggle with mental illness – but few can observe her work without noticing the obsessive, meticulous shapes on large canvases.

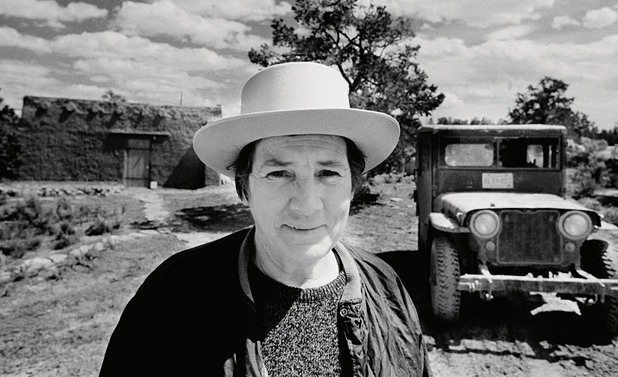

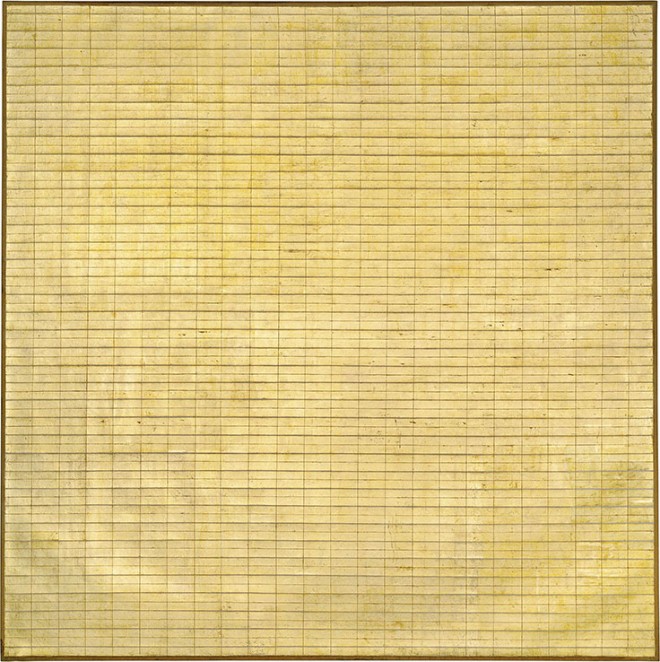

The first room is the most peaceful, as the viewer is automatically drawn into her world. These luminous and silent paintings are a beautiful example of her signature style of horizontal bands of color. While her style was largely influenced by Miró and Rothko, Martin’s status as a female artist resonates through her subtle choice of color, ranging from a peach-coral to light blue.

Agnes Martin was born to Scottish Presbyterian pioneers in 1912. She believed that she was hated as a child. Martin told her friend, the journalist Jill Johnston, that she had been emotionally abused. Silence was her mother’s weapon and she used it ruthlessly. This sternness ultimately instilled self-discipline in Martin and the enforced solitude fostered her self-reliance.

She did not decide to become an artist until the age of 30. In 1957, art dealer Betty Parsons saw Matin’s paintings in Taos and offered to represent her if she moved to New York. Matin attended Columbia and the change in her artwork was drastic.

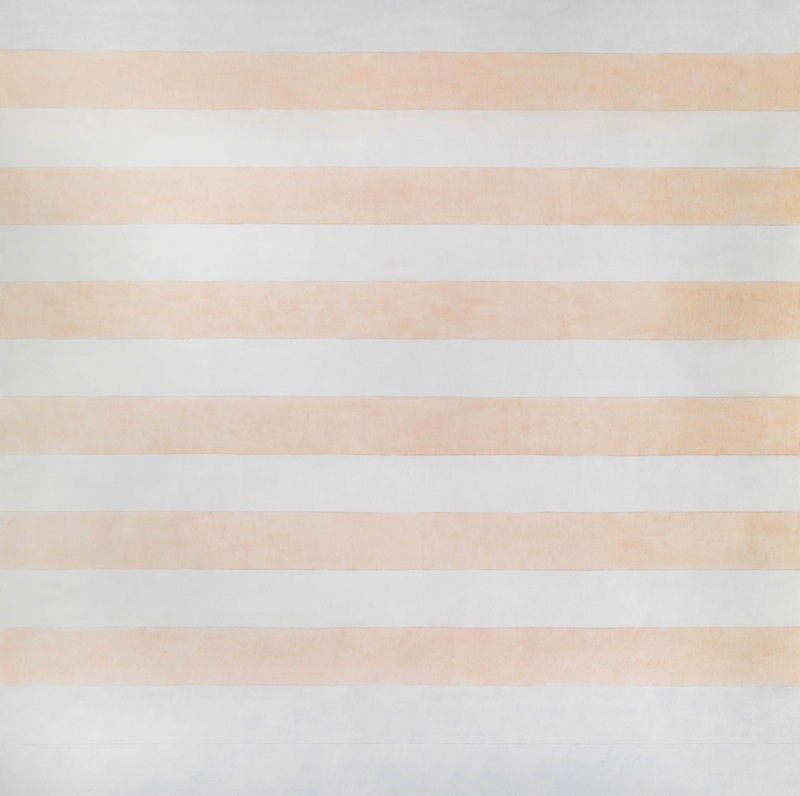

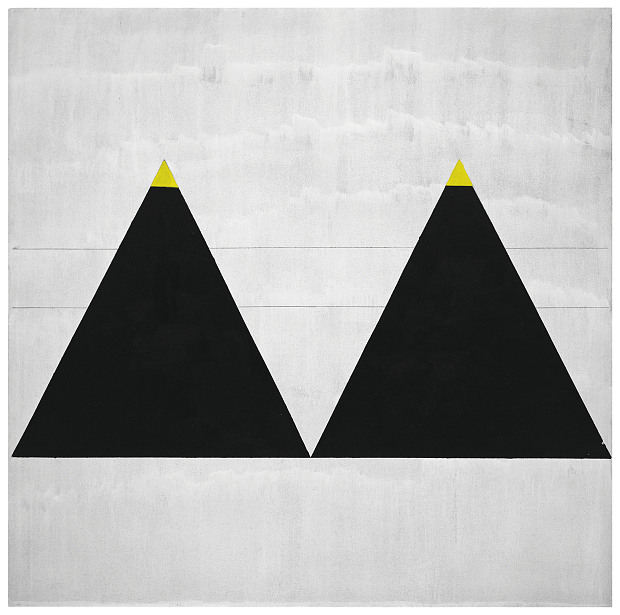

In 1967, Martin gave up making art for five years because of her struggle with schizophrenia. She sold her possessions and travelled around North America in a van. Some of the paintings made in the preceding years take on a clinical aspect. The backgrounds are a starker white, the grids in graphite appear like spaces of confinement.

The final room is dedicated to Agnes Martin’s last works. Made just months before she died in 2004 at the age of 92, the paintings are significantly more peaceful. There is something calming about seeing proof of an artist resolving their troubled past at the tail end of their career.

Agnes Martin pursued a compulsive, hypnotic, musical repetition. Her paintings focused almost exclusively on horizontal bars of color, tiny multitudinous grids, lines and shapes. She worked on a painting until it became “acceptable” to her mind. Most of her work has not survived as she would destroy anything that was not “perfect.” Knowing this makes the exhibit at the Tate well worth the long lines.

Like this article? Check out our review of the Jim Shaw retrospective at the New Museum in New York, or other groundbreaking shows around the world.